The Clay Brick and Tile Industry of Mason City, Iowa

From 1871 until 1979, a major industry in Mason City grew, then flourished, becoming at one time among the largest manufacturers in finished clay products in the nation (Loomis 2011). Until the energy crisis of the 1970s, the demand for Mason City clay products was strong enough to survive the coal shortage of 1903 and labor strike of 1909 (Minnesota Bricks 2011) as well as labor shortages caused by the world wars (c.f. Brick and Clay Record 1917).

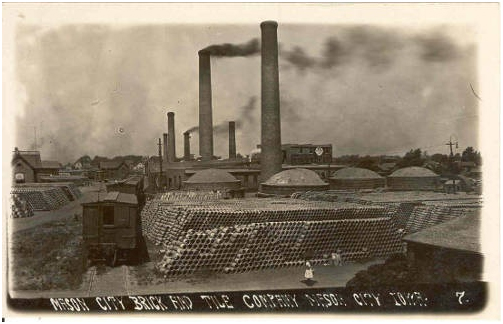

American Brick and Tile Company, Mason City, Iowa. Postcard. California Brick Society

American Brick and Tile Company, Mason City, Iowa. Postcard. California Brick Society

Despite numerous challenges, the combination of labor, transportation, raw material and an active and engaged management lead to great successes. By 1913, a manager of a local brickworks wrote to a trade journal to protest the proclamations made in other areas of the Midwest and to indicate how much more impressive the Mason City operations were:

…a trifle over thirty hollow block chimneys in Mason City, ranging from a 115 to 150 feet high. All but four of these have been put up by a local mason whose name is Joseph Maddy. Overburden Stockpile -Myron W. Stephenson, Gen. Supt. Mason City Brick and Tile Works. (Brick and Clay Record 1913)

The success can be attributed to a combination of local available and abundant raw material and a superior transportation network, especially rail freight. Much of the success of the Mason City Brick and Tile industry was achieved under the leadership of O.T. Denison, who was a proprietor in three of the many of the brick yards, including the largest, the Mason City Brick and Tile Works. Under his direction, the company came to own most of the brick works in town, the North Iowa Brick and Tile Works being an exception. Denison was given the place of primary eminence in the biographical volume of the 1910 History of Cerro Gordo County, Iowa (Wheeler 1910).

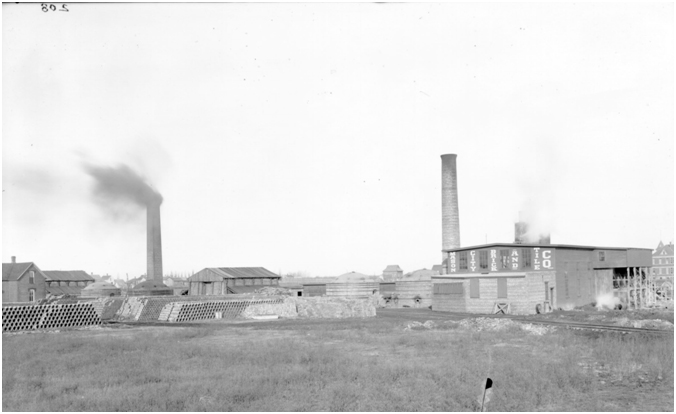

Mason City Brick and Tile Company, Mason City, Iowa. Post Card. California Brick Society

The first Brick fired in Mason City by Nelson Gaylord in 1861 (American Clay Magazine, Bucyrus, Ohio, December 1910, Volume 4, Number 4). It appears Gaylord employed temporary clamp kilns on site. Nels M. Nelson and Henry Brickson opened first brick yard west of the river in the NW ¼ of Section 34, Lime Creek Township in 1871. In 1877 Nelson became the sole proprietor. By 1908 the Northwest States Portland Cement Company was in operation and they would eventually obtain the same land parcel. By then Nelson had moved to SW Mason City.

In Iowa, like much of the Upper Midwest, Clay is an abundant mineral resource, occurring in loess-deposited windblown and colluvial sediments, river valleys as alluvial sediments, and in sedimentary clay shale rock formations such as those present in the Mason City area. Clay and clay shales are used in brick, tile, and pottery manufacture but also as components of cement manufacture and specialty applications (Anderson and Bunker, Anderson 1998). In Mason City, brick and tile and cement were and are the main uses of locally mined clay and clay shale.

Clay pit of the Mason City Brick and Tile Company, Geologic Age: Devonian, Lime Creek Shales., Photographed by: Samuel Calvin. Photograph No. 91, Calvin Collection, Iowa Digital Library

Clay pit of the Mason City Brick and Tile Company, Geologic Age: Devonian, Lime Creek Shales., Photographed by: Samuel Calvin. Photograph No. 91, Calvin Collection, Iowa Digital Library

Naturally occurring industrial grade clay shales of Lime Creek Formation of the Devonian system and lacustrien lake deposits are present at Mason City, along with Sioux City, Ottumwa, Clinton, and Van Meter, Dallas County (Anderson 1998). In the 1920s there were more than 300 brick and tile works in the state.

Samuel Calvin was educated in classical studies and natural sciences. A self-trained geologist, Calvin eventually earned a position on the faculty and taught at the State University of Iowa, now known as the University of Iowa, in Iowa City. He was interested in the applied sciences of Geology. Several photos in the Samuel Calvin collection at the University of Iowa Libraries show images of the early brick and tile works facility. The images document production facilities, products made, the name of the company and the clay mine operations.

The type of raw material has much to do with the final product that is derived from the material. For instance, raw clay derived from loess or alluvial sediments most often forms an earthenware used in soft brick and drain tile while clay shales are useful in high-fire, hard materials such as face brick, fire brick (refractory brick), brick pavers and has the name of flint clay, fire clay, stoneware and so on. More to the point, clays that have accumulated due to geological mechanical transport tend to be higher in oxides, especially iron, as well as mixed with impurities such as organic matter. These clays therefore have a much lower refractive nature, meld at a lower temperature, but remain porous when fired and perform poorly under high kiln temperatures. Conversely, clays that form in one place due to the chemical or mechanical leaching of soluble materials and leaving the clay deposits as residual accumulations tend to be low in oxides and in localized areas are free of impurities, and therefore are less plastic and more refractive. These clays tend to be nearly pure derivatives of feldspar and perform well at high temperatures, become fully fused (vitreous) and approach glass in final characteristics when fully fired. There are exceptions and it is based more on parent material and the presence of the impurities than anything else but in general primary weathered sedimentary materials and weathered igneous form the most pure clays—i.e., kaolin (Searle 1912, Rhodes 1973). Ball clay is secondary clay that is extraordinarily free of iron and sand and therefore is an excellent plastic additive for Kaolin, which is too stiff for most applications. Using a variety of clay types and other material additives, stone grit, previously fired clay grog, sand, and so on can also allow clays to be designed for specific purposes. Brick and tile industrial applications favor iron–rich, natural accumulations of soft clay that has or to which an appropriate amount of sand can be added without too much trouble (Rhodes 1973).

Initially, brick was made in clamp kilns on a building site, after the basement cellar had been dug. According to experts in the plaster industry, building pits are also useful in that industry as well. For this, limestone was needed on site or needed to be brought to the site. Both brick and plaster require a considerable amount of fuel to make. Later, kilns were built and were first fired with wood.

The conversion to coal was likely for mixed reasons. First, wood had become scarce by the late 19th century. Importantly, the writer’s for the Calvin Project at The University of Iowa Libraries observed the denuded landscape in late 19th century Iowa, remarking that

Most striking and useful for geologic interpretation is the lack of trees in Calvin’s photographs. The pioneers and industries consumed most of the trees for buildings and fuel. Today, Iowa is more wooded, and many of the geologic localities that Calvin photographed, as well as the new roads and railcuts, have since been overgrown or lost to new construction. The photographs are potentially useful for the study of agricultural changes and land use. They give a glimpse of the native prairie that existed in Iowa in the late 1800’s. (Iowa Digital Library 2011)

And although large scale industrial brick works require coal to fire the kilns and as source of power to run pug mills, mixers, and extruders (Weitzel 2005, Bleininger and Greaves-Walker 1918, Windsor and Kinfield Publishing Co 1897–ca.1950), there were a number of issues when converting to coal but also expanding it as a fuel source (Dornback 1910).

In 1866, the Mason City and Fort Dodge railroad line was established. The railroad opened the door for Mason City to grow quickly providing transportation for people, raw materials and finished goods. The first to make use of these factors was the Mason City Brick and Tile Company (Visit Mason City, Iowa 2011).

The Mason City Brick and Tile Co. brick works plant was located inside the corporate boundary, in the south part of the 3rd Ward at the time. It began operations in 1892 (Brick and Clay Record 1909). The location was northwest of the Elmwood Cemetery at a location corresponding to SW ¼ of the SE ¼ of Section 9. The Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad was shown running east to west near the south section line. The intersecting line from the southwest was operated by the Mason City and Fort Dodge Railway. Further east a north to south line was operated by the Iowa Central RR, the Mason City Junction was located near the SW corner. The Brick & Tile plant was serviced by a rail spur from Chicago Milwaukee and St. Paul Railroad. The Patron’s directory listed the Mason City Brick and Tile Company as “Manufacturers of Wire Cut Brick and Drain Tile, Vitrified Paving and Sidewalk Brick, Dealers in St. Louis Firebrick and Fire Clay. O.T. Denison President and Manager.

View of works of the Mason City Brick and Tile Company, from the southeast. Photographed by: Samuel Calvin. Lantern Slide No. 1481. Photograph No. 98. Calvin Collection, Iowa Digital Library

View of works of the Mason City Brick and Tile Company, from the southeast. Photographed by: Samuel Calvin. Lantern Slide No. 1481. Photograph No. 98. Calvin Collection, Iowa Digital Library

In 1909, an additional plant in operation by the American Brick and Tile Company was located 2 miles southwest of the post office, in the NW ¼ of Section 17, due south of the west boundary of Elmsly and Adam’s Subdivision located south west of First Street and Inland Ave in the NW ¼ of the NW ¼ of Section 16 (Sanborn 1909). In 1912, the county atlas depicts the North Iowa Brick and Tile in operation in the SE ¼ of Section 8. The Farmers Cooperative Brick and Tile Co. was located in the west half of the same section. By 1930, the Hixson plat map and trade journals indicate there were 10 plants operated by 8 companies.

Originally, clay was dug by hand and most brick works used human or animal power to move barrows or carts of clay to the brick works (Lienhard 1997, Terrell 200, Webber 1976–1992). Depending on the type of clay, the amount of impurities or inclusions and the desired final product, different processes were used. Some clay works will spread out the raw material to dry, sieve, and then crush, re-sieve and rehydrate. This process allows consistency by using a dry weight measure, in turn facilitating more precise mixtures of clays (Rhodes 1873, Weitzel 2005). For extrusion products, the clay would be mixed with other additives to facilitate the process (Propst and Clark 2003). The resulting slurry would then be fed into an extruding machine. This machine could be fitted with differently sized or shaped dies for square building block or round drainage tile. A different type of process was necessary to make silo tile or sewer brick because these generally are made in the form of an arc, the diameter of which determines the size of the final structure. The extrusions were cut in the desired lengths, usually 12 to 14 inches for drain tile, longer for sewer tile. Building blocks were typically sixteen inches (Propst and Clarke 2003). The specialty fittings were of necessity made by hand. Originally, brick was also made by hand using a specialized set of tools and molds (Terrell 2000, Lienhard 1997, Weber 1976–1992, Weitzel 2005).

Eventually, the dry process of pressed bricks was developed, wherein a ball with a clay body containing a lot less water is placed into mold and the pressed into the desired shape using force from any of a number of methods. The tiles were placed on drying racks before being fired in the kilns. Depending on the type of kiln, the bone ware must either be handed onto ware carts, moved to the kiln and it loaded. After a cooling period the tile was removed from the kilns and either stockpiled or loaded directly into boxcars. Later innovations involved rail cars and tunnel kilns. In this process the formed ware is loaded onto rail cars and the cars slowly move through a long, multi-chambered kiln, with each chamber set to the proper temperature to correctly fire the ware from bisque through to vitrification. Today, the process of extrusion to the final shipping point is one long rail with drying and cooling and even glazing accomplished without rehandling the ware. The brickyard would shut down for a short time each winter for repairs and improvements.

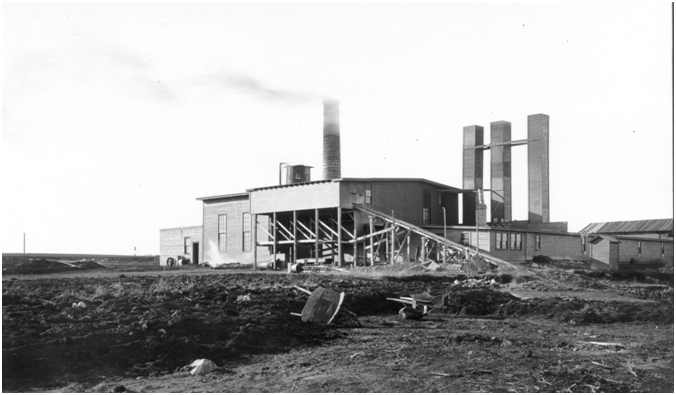

Mason City Brick and Tile Company, view from northeast. Photographed by: Samuel Calvin. Photograph No. 81. Calvin Collection, Iowa Digital Library

Mason City Brick and Tile Company, view from northeast. Photographed by: Samuel Calvin. Photograph No. 81. Calvin Collection, Iowa Digital Library

Eventually, several of the Mason City brick works installed steam powered cable cars made by the Vulcan Iron Works, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania or the Hathorn Foundry & Machine Co., Mason City that were elevated to the top of the clay works by a mine tipple (Brick and Clay Record 1909). When under mutual ownership, several plants would mine from the same pit. As distances grew and labor shortages mounted during WWI, improvements in efficiency for labor and energy drove the further mechanization of the plants and mines.

The Mason City Brick and Tile Works Company installed a rail track with mine cars driven by a steam locomotive some time before 1915 (Propst and Clocke 2003, Sanborn Map 1915). The introduction of steam powered, later diesel powered, draglines and the conversion from coal to gas fired kilns was at this time but were not perfected until the 1920s. At the same time other efficiencies increasingly were introduced, such as hydraulic presses for face brick (Brick and Clay Record 1917, The Clay-worker 1922). Again changes came about as the Second World War approached. The haul line was electrified in 1940 and two side dump engines were purchased from The Clinton, Davenport & Muscatine Railroad (Ross 2011). The engines were made by the Differential Steel Car Company of Findley, Ohio, a company that developed innovations in mine cars and locomotives (Ohio Vintage Coal 2009). When the pits were located farther away from the factories, the rail line was not extended. Instead trucks transported it from the pits to the railhead (Popst and Clocke 2003). View of Differential Steel Car purchased, from the Clinton Davenport & Muscatine Railway. Photograph from the Don Ross Collection (Ross 2011)

View of Differential Steel Car purchased, from the Clinton Davenport & Muscatine Railway. Photograph from the Don Ross Collection (Ross 2011)

By 1956, the transportation of clay to the factory was done all with trucks. Consequently, the rails were removed and the rail equipment was scrapped (Propst and Clocke 2003). By 1979, the demand for brick had greatly reduced demand for the products and the last of the operations ceased.

Components of a Typical Clay Brick or Tile Facility

Clay Pit

Processing Plant/Brick Works

Machine Room/Black Smith Shop/Clay Room

Crushing and pulverizing mills, Mixers, Pug Mills, Extrusion Mills, Brick Press and molds, Conveyors, Ware Cars/tracks, Ware Shelving

Power Plant (to generate steam and electricity)

Drying Sheds

Kiln Array

Offices

Storage/Warehouse

Drying Sheds

Additional

Cable Car/Railroad/Haul Road

Pit mine conveyors/tipple

Tunnel system to duct heat from furnace fire rooms to kilns and drying shed

Steam powered Corliss type engines to haul equipment and for the use of the Power Take Off. The manufacturers were located at Sioux City and Burlington, IA

Products: Pavement brick (street and sidewalk types), drain tile, structural tile (wall block, window caps, window sills, farm silos), common brick (structural brick), hollow brick (face brick).

| Company Name or Other | Significant Dates | Board or Management | Location |

| Lime Creek Brickyard

|

1871 (1)

1882 (8, 5) |

Nels M Nelson and Henry. Brickson to 1877, Nelson sole proprietor after 1877

N.M. Nelson and Barr |

First pit and works were in Lime Creek Twp,

NW-34-97-20 Later moved to Southwest Mason City in 1882. 4,000 brick from this yard in 1882.

|

| Mason City Brick and Tile Company

Later acquired the American Brick and Tile Company and consolidated the Denison companies under this name, 7 facilities

|

1884 (2) (founded)

Incorporated 1892 (2) |

O.T. Denison, President and L.W. Dension Secretary-Treasurer | SW-SE-9-96-20 |

| 1910 (4) | C.E. Smith General Manger | ||

| Added Clay handling plant in clay pit and tramways before 1914 | 1913 (4) | M.W. Stephenson General Superintendent | |

| 1914 (8) | Keeler consolidates four operations into one company | ||

| American Brick and Tile Company

Built on site of the original Nelson and Barr brick works of 1882 (5) Second Plant (Plant No. 1), due north across railroad track.

|

1900 (6)

1910–1914 (7)

1914 (7, 8)

|

Ira Irving Nichol Organizer

Albert F. Shots General Manger

Both acquired by MCB&T |

SW-SW-9-96-20 |

| Farmers Cooperative Brick and Tile Company

Same proprietor in Sheffield |

1910 (3) | James H. Brown

William M. Colby (Promotional Agent)

|

SE-SW-8-96-20 |

| Mason City Drain Tile Company

Built second plant |

1907 (2)

1914 (7, 8) |

O. T. Denison, president; F. A. Stephenson, vice-president; F. E. Keeler, secretary, and L. W. Denison, treasurer.

Acquired by MCB&T

|

NE-NW-16-96-20 |

| Mason City Sewer Pipe Company

Sewer tile and brick.

Completely lit by electrical lights when built

|

1905 (2)

1914 (7, 8) |

O.T. Dension, president L. W. Denison, secretary, and F. E. Keeler, treasurer.

Acquired by MCB&T |

SE-SW-8-96-20 |

| Mason City Clay Works

Drain tile, common brick, and hollow block tile. Uses cable cars built by Vulcan Iron Works, Wilkes-Barre, PA This company used mechanical explosives to loosen shales that they worked to a depth of 45 feet below surface. (2)

|

1900 (2)

1914 (7, 8) |

F. A. Stephenson is president; O. T. Denison, vice-president; L. W. Denison, secretary, and F. E. Keeler, treasurer. Stephenson also had work or was working with plants in Des Moines and Illinois

Acquired by MCB&T |

NW-NE-16-96-20 |

| National Clay Works | 3 Miles west of Court House(7) | ||

- Lime Creek Township. Union Publishing 1883

- Brick and Clay Record 1909

- Brick and Clay Record 1910

- Brick and Clay Record 1913

- The Iowa Engineer, Iowa State College, Ames, Iowa, October 1910, Volume XI, Number 1

- Wheeler 1910

- Sanborn Maps

- Loomis 2011

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, R.R. and B. J. Bunker Fossil Shells, Glacial Swells, Piggy Smells, and Drainage Wells: The Geology of the Mason City, Iowa, Area, GSI-65, Iowa Geological Society, Iowa City 1998.

Anderson, Wayne l. Iowa’s Geologic Past: Three Billion Years of Earth History. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City. 1998.

Becker, Sharon R. Cero Gordo County, IaGenweb Project. Accessed September 22, 201

Bettis, E. Arthur III. Soil Morphological Properties and Weathering Zone Characteristics as Age Indicators in Holocene Alluvium in the Upper Midwest. Chapter 4 in Holliday, Vance T. Soils in Archaeology: Landscape Evolution and Human Occupation. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. 1992.

Bleininger, A.V and A.F. Greaves-Walker. Fuel Economy in Burning Clays. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1918

California Brick. Historical Brictures, California Brick Society Website, http://californiabricksociety.com/HistoricalPictures.html, Accessed September 23, 2011.

Cerro Gordo County Assessor website http://www.co.cerro-gordo.ia.us/WebAccess/showimage PDF.asp?docid=10000000042000026809, Accessed September 22, 2011.

Dornback, W.E. The Iowa Engineer, Iowa State College, Ames, Iowa, October 1910, Volume XI, Number 1

Hirst, K. Kris. Archaeological Investigation at the Brown Brothers Tile Factory, Washington County, Iowa. Journal of the Iowa Archaeological Society. Vol. 47. 2000.

Brick and Tile Bibliography. Brick and Tile References: Technical Treatises for the Archaeologist. Tennessee Archaeology Net Bibliography Page. Frank.mtsu.edu/~kesmith/TNARCHNET/Pubs/Bricks.html. Accessed September 23, 2001.

Hixson. Plat Book of Cerro Gordo County, Iowa. W.W. Hixson & Company, Rockford, IL. 1930. Copy available at Iowa Digital Library http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/u?/hixson,297. Accessed September 23, 2011

Iowa Digital Library, Calvin Image Database, Digital Library Services, The University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City. http://www.uiowa.edu/~calvin/calvin_search.html. Accessed September 23, 2011.

Iowa Geographic Map Server, Iowa State University Geographic Information Systems Support & Research Facility, Ames, Accessed September 22, 2010

Iowa Geological and Water Survey web site, Bedrock and Quaternary Geologic and Maps of Iowa, Iowa Department of Natural Resources web page, Accessed September 22, 2011.

Lienhard, John L. Engines of Our Ingenuity. No. 1249, Bricks. http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi1249.htm. Accessed September 23. 2011.

Minnesota Bricks, 10 – Out of State Brick, Iowa Brick, Mason City Brick, http://www.mnbricks.com/mason-city-brick, MNBricks.com, 2011. Accessed September 23, 2011.

National Brick, The Clay-worker, Volumes 77-78, National Brick Manufacturers’ Association of the United States of America, Indianapolis. 1922.

North West Publishing. Plat book of Cerro Gordo County, Iowa. North West Publishing Company, s.l. [probably Philadelphia], 1895. Copy available at Iowa Digital Library http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/u?/atlases,644. Accessed September 23, 2011

Ohio Vintage Coal, Differential Steel Car Co., http://industrialrail.5u.com/photo_44.html, Ohio Vintage Coal Company, Pataskala, Ohio, 2009. Accessed September 23, 2011.

Online Iowa Site File database and LANDMASS predicative and interpretive models, Office of the State Archaeologist, The University of Iowa,

Prior, Jean C., Landforms of Iowa, The University of Iowa Press, 1991

Propst, Clark and Chuck Klocke, “27) Mason City Brick and Tile Works”, Chuck Klocke contributor. Minneapolis and St. Louis Railway Company: Mason City Industry by Clark Propst on Minneapolis & St. Louis, Iowa Central, Chicago & Northwestern Website, Lyndon “Cash” Groth on RailServe, Internet Railroad Database. http://www.cashgroth.com/index.html. 2003, Accessed September 23, 2011.

Rhodes, Daniel, Clay and Glazes for the Potter. Chilton Book Company, Radnor, Pennsylvania. 1973.

Ross, Don. Mason City Brick & Tile Co., Mason City Brick & Tile Company, Don’s Rail Photos, http://donsdepot.donrossgroup.net/dr145.htm,Don Ross Group. 2011. Accessed September 23, 2011

Searle, Alfred B. The Natural History of Clay. Cambridge University Press, G.P. Putnum,’s Sons New York, 1912.

Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Web Soil Survey. Available online at http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/. Accessed September 22, 2011.

Terrell, Michelle M. Nineteenth Century Soft-Mud Brick Kilns: Two Examples From Lost Creek Valley, Mahaska County, Iowa. Journal of the Iowa Archaeological Society. Vol. 47. 2000.

Union Publishing, History of Franklin and Cerro Gordo Counties, Iowa, Union Publishing Company, Springfield, Illinois. 1883.

Visit Mason City, Iowa. About Mason City: Mason City History, Visit Mason City, Iowa website. http://www.visitmasoncityiowa.com/html/history.htm, Accessed September 23, 2011.

Wall, Joseph Frazier. The WPA Guide to 1930’s Iowa Pp. 285-88. Federal Writers Project. University of Iowa Press. Iowa City. 1986.

Weber, Irving. Historical Stories about Iowa City (Irving Weber’s Iowa City). Lions Club (Iowa City, Iowa). 1976–1992.

Weitzel, Tim, An Armchair Walking Tour of the Longfellow Neighborhood, Library Cable Chanel 4, August 1, 2005, Iowa City Public library, Iowa City. 2005

History Notes: The Oakes Brickworks and “1142” in The Long View [Newsletter], Longfellow Neighborhood Association, November 2005, Iowa City, Iowa. 2005.

The Longfellow Neighborhood Historic Markers, in Past, Present, Future, Spring 2005, Friends of Historic Preservation, Iowa City, Iowa. 2005.

The Oakes Brickworks, Sign #2B, Longfellow Neighborhood Art Project. Historic Markers and Public Art in the Longfellow Neighborhood, Iowa City. http://www.icgov.org/default/?id=1684 and http://www.icgov.org/site/CMSv2/file/publicArt/LNAbrochure.pdf, Accessed September 23, 2011, City of Iowa City, Iowa City, Iowa. Updated 2008.

Wheeler, J.H., History of Cerro Gordo County Iowa, Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago. 1910.

Wikipedia online encyclopedia (www.wikipedia.org). Accessed; September 22, 2010

Windsor and Kinfield Publishing Co. Brick and Clay Record, Windsor and Kinfield Publishing Company, Chicago, 1897–ca. 1 950.

Volume XX, Number 2, Page 93, February 1904

Volume XIX, Number 2, Pages 4, 41, August 1903

Volume XXX, Number 1, Pages 1, 11, 12, 13, 14, January 1909

Volume XXIX, Number 6, Page 532, December 1908

Volume XXIX, Number 2, Page 345, August 1908

Volume XXXIII, Number 3, Page 135, 121, September 1910

Volume LI, Number 1, Page 692–693, July, 1950