Home » Posts tagged 'Physics'

Tag Archives: Physics

University Space: Van Allen Hall as an Example

In October 1963, ground was quietly broken for a major research and education center near the heart of Iowa City, Iowa. The cold war dominated politics and space science was in its early days. Popular culture was catching on to ideas of space exploration. As

![Van Allen Hall Exterior (11) [Web Large]](https://timweitzel.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/van-allen-hall-exterior-11-web-large.jpg?w=506&h=338)

Van Allen Hall, view facing southeast. Tim Weitzel

hallmarks of the Space Age, the popular band The Tornadoes’ instrumental ode to a satellite, Telstar, played on the radio, the Jetsons played on American television, and the science fiction hit film Dr. No, which was about a scientific genius bent on destroying the United States Space Program, played in the theaters.

Real life was only slightly less exciting. The first robotic probe to reach another planet, Mariner 2, had reached Venus in January. American Gordon Cooper orbited the earth for 34 hours in March, and in June, Soviet Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in Space. This cultural milieu resulted from the Space Race, intensified in no small part by President Kennedy’s 1961 address to Congress.

Echoing Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1957 announcement to launch a United States satellite during the International Geophysical Year, John F. Kennedy made a pledge to land an American on the Moon by the end of the 1960s. As a result, Congress had made grant funding for space programs more widely available. And despite the push for an American to be the first human on the Moon, James Van Allen played a large role in keeping a national focus on science probes even as the public eye was caught by the perhaps more relatable idea of people in space. The push for pure science lead to a need for more space to build instruments and interpret results. Ultimately this space would arrive and become Van Allen’s namesake.

But it was not an easy road to get to the point of building the new building. It had taken five years of funding requests, negotiations, and planning. As head of the department, James Van Allen (1914–2006) had been seeking necessary additional square footage following the department’s success with the first space physics experiment conducted by anyone on Earth.[1]

A Proposal to Expand

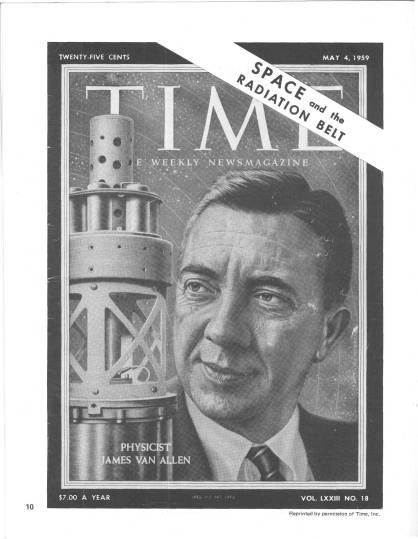

The initial plan for expansion of the facilities for the University of Iowa’s Physics Department began in 1958 when space for research, teaching, and building space instruments was already tight in MacLean Hall (1912).[2] In January 1958, the University of Iowa instrument onboard the Explorer I probe—a Geiger-Müller tube connected to a

Van Allen on the cover of Time Magazine, May 4, 1959. Reprinted in Iowa Alumni Review, v. 34, no.2, 1981

radio transmitter, recorded what Van Allen intended to be ionizing radiation from cosmic rays, but instead, he and his graduate students determined that they had found radiation belts around Earth. Through the 1960s, Van Allen and others would theorize, and eventually explain, that the Van Allen radiation belts were caused by the interaction of the Solar wind and the Earth’s magnetosphere. But that work had yet to be completed.

At the end of the 1950s, the growth of space exploration meant more funding for research, but that meant more room was necessary to design and build space instruments and interpret data. With enrollment still increasing in part due in part to the Long Economic Boom but also due to the resulting changes in job expectations, the need for additional classroom space was also an issue. Student enrollment increased about 31 percent from 1955 to 1960.[3]

At least partially due to the interest in space exploration, enrollment in physics courses increased at a far greater rate than had been anticipated when the MacLean Hall had been designed.[4] Nuclear weapons and requirements of expanding industry cannot be discounted as factors while physics also was increasingly seen as part of the general education curriculum for a Liberal Arts college degree.[5] Scheduling conflicts in the use of the building’s limited area were occurring between the math faculty and the physics faculty throughout the building.

George Ludwig with Data Reduction Equipment, MacLean Hall, around 1960. Frederick W. Kent. Iowa Digital Library, University of Iowa Archives

The crowded conditions of MacLean Hall in the late 1950s were well known to the scientific community of the United States.[6] The publicity that Van Allen’s department had gained with the Explorer I discoveries meant visitors of many types from many places periodically squeezed into the space science workshop at the end of the basement hallway of the 46-year-old building.[7]

Van Allen campaigned for more research and office space to support the research of the department. With the support of university president Virgil Hancher, a concept sketch was drawn by university architect Richard R. Jordison on August 19, 1958.[8]

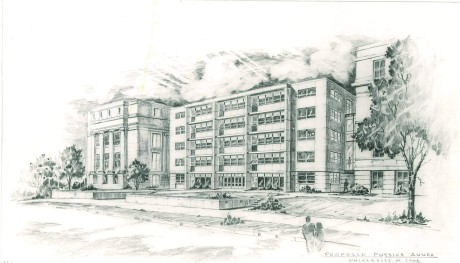

Proposed Physics Annex, University of Iowa. Concept sketch by Richard R. Jordison, August 19, 1958. Iowa Digital Library, University of Iowa Archives.

Interestingly, the view of the south elevation of the proposed building was labeled Physics Annex while the view of the north elevation was labeled Physics-Mathematics Building.[9] The significance of this difference is subtle and easy to overlook, but it indicates a duality that Van Allen continued to work with in the years to come.

Perspective from Capitol.

Proposed Physics-Mathematics Building, University of Iowa.

Concept sketch by Richard R. Jordison, August 19, 1958.

Iowa Digital Library, University of Iowa Archives.

In 1959, with Van Allen as department chair, astronomy staff and faculty were added to the department and the name changed to Department of Physics and Astronomy.[10] But the astronomers wouldn’t have to move at all to join the physics team because they were part of the Math Department, which was also located in MacLean Hall. Since 1860, math professors at the University of Iowa had taught astronomy.[11] MacLean Hall had been shared among the Mathematics and Physics departments from 1912 when it was completed. As a result, the proposals for a new Physics building contained an option, if not outright expectation, for shared space.

The concept for the proposed building included modular space that could be reconfigured with movable walls.[12] The five-story building was to be placed between Schaeffer Hall and MacLean Hall with walkways to connect to both buildings on the second and third floor.[13] The proposal was expected to cost between $100,000 to $250,000 out of a total request for $9.5M for eight University of Iowa projects submitted for funding.[14]

The new building was intended to include basement laboratories for physics as well as a new math library, mathematics and physics offices, and mathematics classrooms. The idea was also floated that the classrooms could be used by the academic departments in Schaeffer Hall (1898).[15]

President Hancher submitted the elevations and plans to the Board of Regents on behalf of the state university. The Regents approved the proposal along with the budget requests from the Iowa State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts—now Iowa State University and the Iowa Teachers College —now the University of Northern Iowa. The proposal then went to the Governor for consideration and approval. From there, a budget request would be submitted to the legislature.

Governor Herschel Loveless, a fiscal conservative who was intent on reducing government spending, cut the Regents $29M funding request by $15M, or a little more than half the amount the Regents had asked for.[16] Out of that amount, the Iowa Legislature approved $6M specifically for the University of Iowa, including a new law building, chemistry building, and pharmacy building but for reasons that aren’t clear, not the Physics-Mathematics Building or the business building.[17]

The following year, the Regents returned with the funding request for the new Physics and Mathematics building, now asking $1.5M.[18] In the proposal, the building was now called South Hall and again the shared use among many departments was suggested. The 1959 funding request also didn’t gain the support of the state government.

The reasons for the rejection this time appear to have been a mixture of aesthetic choices and fiscal policy. There were negative opinions about the use of the Pentacrest for the new facility due to the effects the new building would have on the campus design. The Pentacrest was a plan conceived by President Charles Schaeffer toward the end of the 19th century to unify the appearance of the University. The Pentacrest plan included a landscape design by the Olmsted Brothers of Massachusetts and buildings designed by Proudfoot, Bird & Rawson of Des Moines.[19] It is possible the legislature did not want to sacrifice this unified design, which was still in progress. It had taken decades and yet this major campus improvement was not fully complete—the Old Dental Building would not be demolished until 1975.

An example of the negative opinion on campus was evident in the press. One letter to the editor from a university student provided a scathing rebuttal to the idea of a new building there:

Let’s have connecting annexes between all the perimetric Pentacrest buildings. And then let’s spread a huge canvas roof over the entire area and charge visitors for a sight of Old Capitol. The proceeds can be used for constructing additional parking lots. Let’s sacrifice the esthetic beauty of the Pentacrest, but not only for economy and practicality, but also for profit.[20]

Similarly, both the state senator and state representative for Iowa City continued to oppose the placement of the building on the Pentacrest as late as March, 1961. This was despite assurances by university architect George Horner that the new building would blend harmoniously with the existing architecture and would fill a similar position as the old Dental Building between MacBride and Jessup Hall.[21] Horner further posited the principal viewsheds for the Old Capitol were from the east and west. Iowa City’s members of the state legislature were not convinced by this appeal. Senator D.C. Nolan said the placement of the building would “tend to spoil the general view of the campus,” while Representative Scott Swisher suggested an entirely new building, built elsewhere,was in order for the important work being done in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.[22]

It is also clear the governor and legislature as a whole wanted to cut state expenditures, even as Hancher and the Regents annually requested support for an extensive expansion of university facilities. The funding proposal for the new building was based on the concept that the state should pay for all university improvements through tax and other revenues—a position for which it was becoming hard to win support with the state government.

In the face of the legislature’s fiscal conservatism, President Hancher still thought the state should pay for higher education facilities. The University’s funding proposals into 1961 were based on this philosophy. Hancher was wary of federal funding and the potential steering of research goals and interests that might result from external funding commitments.[23] Van Allen conceded this point to an extent, but in characteristic equivalence, he also saw no universal problems with federal funding for research and in fact was skeptical that isolated federal scientists working for the military were likely to ever produce good work.

Van Allen had gained respect among academics and government officials as a research scientist conducting weapons research at Johns Hopkins University and their Applied Physics Laboratory. The University of Iowa had a similar history with a university federal weapons research program and the department as a whole likely shared his views.[24] Van Allen was convinced better military research and science in general was carried out by civilian researchers located in universities.[25]

It may have appeared at the time that funding any new building for physics and astronomy was now at a hopeless impasse. The critics of a new building had set up two problems to solve—external funding and a location off of the Pentacrest. Then in 1960, Herschel Loveless determined he would run for Congress allowing Norman Erbe—lawyer, former mason’s assistant, summer farm hand, and military veteran, to campaign for the open Governor’s seat and win.[26] The combination of the new state leadership, more external funding in the form of federal grants, and a less aesthetically controversial site away from the Pentacrest would prove to be critical to the success of obtaining a new facility.

A New Location Sought

A parking lot at the corner of Jefferson and Dubuque Streets came into consideration for the new Physics and Mathematics building by March 1961.[27] The parking lot under consideration was in many ways ideal. It was near enough to being vacant to be easy to build on. It was also located on the land of a former university building and purchase of the property was unnecessary.

The parking lot was also the location of the former City Park. The park had been included on the original 1839 Town Plat for Iowa City. The original City Park was bounded by Iowa Avenue to the south and clockwise by Dubuque, Jefferson, and Linn streets. In 1890, Iowa City transferred ownership of the park along with the Linn Street right-of-way to the University of Iowa.[28] The park had been a prime location for the University of Iowa to expand in the late 19th century as any other lots near campus required both purchase of privately held property and demolition of the buildings located on the lots.

The park was adjacent to a school reserve that had been granted to the university earlier. The school reserve was located in the half block on the east side of Linn Street adjacent to the city park. The lot had included the Mechanics Academy building where the first courses were taught for the University during the 1857 academic year, including natural philosophy (physics) and astronomy.[29] The Iowa legislature had donated that building to the University of Iowa twenty-four years earlier in 1866.[30] In the last decades of the 19th century the Mechanic’s Academy had been converted to the university hospital. The park was was near the expanding university campus, especially for the interrelated fields of medicine, pharmacy, and chemistry. The medical school at the time was soon to be located along Jefferson Street, just west of Dubuque Street. The university eventually demolished the Mechanics Academy and by 1899 had constructed the first unit of a new university hospital, which was later known as East Hall and then Seashore Hall.

As an experiment in new treatment methods, a homeopathic hospital was built at the southeast corner of Dubuque and Jefferson Streets on the newly acquired park block, in

State Homeopathic Hospital,

postcard image from Medical Museum, University of Iowa

1894.[31] This is the location of Van Allen Hall today and at the time was close to other medical facilities. That building was of brick construction and measured 75 feet by 60 feet and stood three stories tall. The small hospital included a lecture room and 54 beds.[32] In 1919, the Homeopathic Hospital was closed and the building became an annex to the nearby main hospital building. The Hospital Annex had a major fire in 1929 and was demolished.[33] Following this, the north half of the old park became a parking lot with only East Hall Annex remaining on the block.

Also in the 1890s East Hall Annex, originally known as the Chemistry building and soon after the Hall of Chemistry and Pharmacy, was built south of the 1894 homeopathic hospital at the northeast corner of Dubuque Street and Iowa Avenue, joining the early

Hall of Chemistry and Pharmacy,

Samuel Calvin, date unknown.

Iowa Digital Library, University of Iowa Archives

20th century medical buildings on east campus.[34] Following the relocation of the medical campus to the west side of the river, this building passed through many departments including Electrical Engineering and was last known as East Hall Annex before it was demolished in the summer of 1973. The building had been condemned for fire safety reasons 12 years previously while it was still being used by the Electrical Engineering Department due to funding issues.[35] This building was three stories tall and made of brick. The footprint measured 150 feet by 105 feet.[36] Because of its location, this building would prove to be significant in shaping the form of the new physics building.[37]

The parking lot site for a new Physics-Mathematics building was also located just north of the proposed location for the Nuclear Research Laboratory on Dubuque Street, for which funding had been approved for the equipment.[38] Hancher soon indicated the site was being considered for an eight- to ten-story general use building that would house the Physics and Mathematics Departments as well as the College of Business Administration and possibly electrical engineering.[39]

But this building proposal also had its critics. The building was thought to be too tall. Citing a recently constructed building at Indiana University, university architect George Horner asserted that tall buildings were inefficient and that hallways and elevators would be overly crowded in this type of facility.

Ultimately, extensive grant funding for facilities was obtained and a single, tall university building to house three or more departments would not be necessary. With separate sites and funding available for the other major departments, Van Allen and Hancher returned to a plan for a new physics and mathematics building, with possible shared space with Electrical Engineering.

External Funding Sources

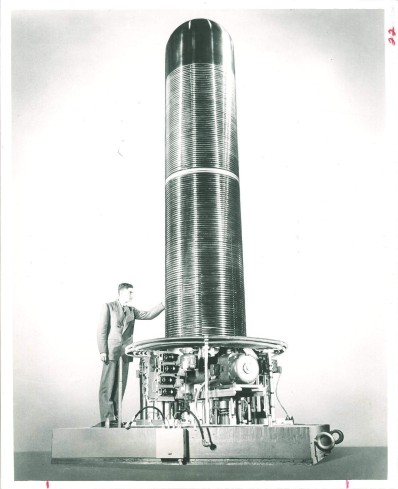

Efforts to secure external funding ran tandem to selecting a site for the new building. But before the new building was approved, the Department of Physics and Astronomy prepared a grant proposal for a three- to six-mega electron volt (MeV) Van de Graaff linear accelerator. The funding for the accelerator is significant when looking at the events leading to funding of Van Allen Hall.

In the early 1960s, the University of Iowa was a leading institution not only in space physics but also nuclear physics, though Hancher publicly argued the equipment was lagging behind other institutions. This represented a remarkable accomplishment for Van Allen as chair of the department and whose PhD thesis had been on a topic in Nuclear Physics. The new accelerator would be used to test fundamental physics of baryonic matter—matter composed of standard atomic nuclei, and put the University of Iowa back at the forefront of nuclear physics.[40]

At that time, little was known about atomic structure, especially with regard to subatomic particles, or the potential existence of dark matter. While the comparative power of an electron volt (eV) is small, the ions or particles accelerated are small as well. Therefore the resulting ions can be propelled at a considerable fraction of the speed of light allowing the strong nuclear bond in the nucleus to be broken and separating protons and neutrons. For this instrument, the speed was 13,500 miles per second. Studying the resulting collisions provides information, such as mass and charge, of the resulting ions or particles.

The acceleration potential of the accelerator that was built was 5.5 MeV, which was then improved to 6.0 MeV. This is verging on medium-energy collisions but it also approximates particles found in space. Therefore, it was suggested in a press release

The 5.5 MeV Van de Graaff accelerator,1963.

Frederick W. Kent, Iowa Digital Library,

University of Iowa Archives.

that the new accelerator could also be used to scale and test detectors for spaceflight instruments, though it was never used for this purpose.[41] The much smaller 2.0 MeV accelerator was always used for testing purposes but the announcement tied the new accelerator building to the space program.[42]

Professor Richard Carlson would design a metal plate, which was machined in the shops at Van Allen Hall in 1965. The new device could strip all three electrons from a lithium atom to create a three-proton ion that traveled faster and was then used to collide into the other atoms including lithium, beryllium, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen to split them into electrons, protons, and neutrons.[43]

However, as collision energies have increased, so too the size of the collider. By 1987, the university’s linear accelerator was no longer in use because it had no further purpose for research.[44] Particle physics research in 2019 takes place at the Large Hadron Collider with confirmation work conducted at smaller cyclotrons such as the one at FermiLab in Batavia, Illinois—a facility for which Van Allen had submitted a proposal that would have placed the facility in Iowa.[45]

The National Science Foundation award appears to have helped convince the state legislature to fund the building for the accelerator and in the same award, earmark the funding for the first part of the new Physics-Mathematics building. The Regents approved the NSF grant proposal to fund the Department of Physics and Astronomy accelerator equipment in the spring of 1961 along with a recommendation to the state legislature for $300,000 for a building to house the equipment.[46]

In the 1961 legislative session, with an agreement to look elsewhere than the Pentacrest for the Physics-Mathematics building and the potential for matching federal funding, the state legislature appropriated $1,410,000 for a new physics and mathematics building and research observatory.[47] The Nuclear Research Laboratory was funded at the requested level of $300,000 in the same appropriation, for a total project fund of up to $1,710,000.[48] As a comparison, the new Business Administration building (Phillips Hall) was funded at $1,640,000, and the university hospital received $1,776,000 in funding that year.

A grant proposal to the NSF for a five-story Physics Research Center was submitted in March 1962, requesting $750,000 out of the total of some $2.7M estimated for the project total.[49] The proposal called for 35 laboratories for space science, high energy physics, solid state, low energy physics and other research along with office space for research,

![NSF-NASA Grant Proposal - 0003 [web large]](https://timweitzel.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/nsf-nasa-grant-proposal-0003-web-large.jpg?w=730)

NSF/NASA Proposal, 1962, p 1; University Archives,

Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall.

In September 1962, press release announced that the university had received funding under the NSF Sustaining Universities program. It was also noted that the Board of Regents approved preliminary plans for the Physics Research Center as well as a new research observatory, which would ultimately be located southwest of Hills, Iowa.[51] The NSF funding was not the only matching funds that Van Allen was able to win for the new Physics and Astronomy facility. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration had, during the summer of 1962, established a Sustaining University Program under its Office of Grants and Research Contracts.[52]

The NASA program was the direct result of goals established by administrator James Webb.[53] The goal of the program was “to expand university research and training in the space sciences and technology in keeping pace with the Nation’s rapidly accelerating space effort.” The first five grants were made in August 1962 to build research facilities at universities.[54] The NASA program for facilities began in 1962 with just $10 million available. It peaked in 1965 at $45.7 million and was much curtailed in 1968.[55] The NASA funding could be used toward laboratory or other research space, including offices, but could not fund classrooms.[56] Effectively the same proposal material that had been submitted to NSF was submitted to the NASA Facilities Grant program, this time asking for $610,000.[57] Other than the grant amount, only a single page of the proposal was changed.

A week after the approval of the NSF funding was announced, the NASA funding came through. NASA ultimately contributed $535,000 in actual expenditures to the University of Iowa project, which was small in comparison to many other universities over the life of the program, which ranged upward from $2M to $3M.[58] Only Harvard was lower than Iowa at $151,000. The difference in funding level might have been related to the availability of other funding sources, which for Iowa were considerable and included the state appropriation and the National Science Foundation grant.

That a building up to 10 stories tall was ever under consideration says much about the confidence of Van Allen to obtain significant funds to build the facility. His confidence was based in sound reasoning. Given the prominence of the University of Iowa in space science, it would be a sound deduction to conclude that obtaining the two national grants wasn’t a topic long in doubt. Instead, perhaps only the amounts to be awarded were ever uncertain.

The reason for the open flow of federal resources to construct new buildings on campus was due in no small part to the Space Race. Congress favored the improvement of university facilities across the nation as a result. The first artificial satellites, Sputnik I and Sputnik II, were launched in the fall of 1957. Not only was this a political coup for the Soviet Union, the deeper meaning behind these successes was equally vexing. The same Soviet rockets that were powerful enough to place a satellite into orbit could also place an atomic bomb capable of striking a wide range of targets across the world. In January of 1958, The United States followed the Soviet launches with the launch of Explorer I. This event catalyzed policy makers. By July, a signed authorization created NASA.[59] The next year Congressional funding for the National Science Foundation tripled to $134 million.[60]

Then in April 1961, the Soviets successfully sent Yuri Gagarin into orbit. On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy addressed a joint session of Congress. He said,

This nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.”[61]

Congress responded with an immediate 89 percent increase in the NASA budget.[62] The following year Congress approved another 101 percent increase for NASA that Kennedy readily signed into law. Also in 1962, Kennedy secured congressional funding for educational facilities—especially for science, math, and engineering.

In this climate, Hancher oversaw the biggest boom in new construction in University history with 15 new major academic buildings completed during the decade and twenty-one buildings overall constructed on campus between 1959 and 1968—the single largest period of university facilities construction between 1839 to 2006.[63] During this boom separate buildings were completed for Physics and Astronomy (1965) along with the Business College (Phillips Hall, 1965) and an electrical engineering addition (1964) to the engineering building (Seamans Center for the Engineering Arts and Sciences).

But the reason for the success at the University of Iowa in particular to obtain space grant funding was due to the influence of Van Allen.[64] Before the success of Explorer I, Van Allen had been instrumental in designing proximity fuzes for naval weapons during World War II. His contacts from this experience as well as the success of Explorer I and subsequent low earth orbit research led to funding opportunities that he capitalized on. From 1957, he served on committees that directed the future of space science research and he was often the chair of the committees.[65] He was able to tap into Office of Naval Research funding from 1952 through the 1990s to fund research.[66] From 1957, the NSF was also a common source for research activities in the department.[67] Other grants had been obtained from the Atomic Energy Commission and the US Air Force.[68] While it is notable that Van Allen also credited the Long Economic Boom for creating a climate where government funding at the federal level was temporarily much more attainable, his own influence was clearly essential.[69]

During the summer of 1962 Van Allen and Hancher hosted the Space Science Summer Study at the University of Iowa that was attended by the director of the Space Science board as well as Fred Seitz and James Webb, the heads of NSF and NASA, along with around 200 scientists from around the country representing universities, research corporations, and the government.[70]

Space Science Summer Study 1962. From the left, Fred Seitz, NSF president; University of Iowa President Virgil Hancher; James Webb, director NASA; Hug Odishaw, executive director of the Space Science Board, NSF; James Van Allen, head of Physics and chair of the Space Science Summer Study. Iowa Alumni Review, October 1962.

The top-secret plenary sessions to discuss the future of the US space science were held in Shambaugh Auditorium in the Main Library.[71] It is highly unlikely that the two representatives of the Iowa space program didn’t at some point discuss the grant proposal submitted earlier that year during the scheduled or unscheduled activities of the event. Van Allen capitalized on widespread publicity of the cramped facilities at Maclean Hall following the 1958 success of Explorer I. James Wells wrote in 1980,

It was pointed out that Van Allen’s [space science] people were forced to do their work in a cluttered basement hallway.[72]

In the announcement of the funding approval, the Daily Iowan ran an illustration that indicated a second building matching the first unit of Van Allen Hall would be located where East Hall Annex was located, at the time still occupied by Electrical Engineering.[73] The accelerator building would be located in between the two larger wings. In the grant proposal, however, the second building was located on a north-south axis between the proposed location of Van Allen Hall and Seashore Hall.

Drawing of Proposed Building. Artists sketch of the proposed Physics-Mathematics Building as it appeared in the Daily Iowan, Nov 14, 1962.

While the building proposed in the grant proposal was named the Physics Research Building, which would later be officially named the Physics Research Center, on the public side it was still labeled as the Physics-Mathematics building for approximately one more year.[74] The continued use of the dual idea of a new physics building that ran tandem to a shared facility with mathematics emphasizes Van Allen’s resourcefulness and ability to plan based on multiple contingencies and audiences. The caption for the sketch suggested the second building was for general use, which may have been an appeal toward resolving the earlier proposal for the eight- to ten-story general use building but also allowed for the demolition of the old Chemistry-Pharmacy building.[75]

On November 14, 1962 the Daily Iowan reported “University of Iowa Gets $650,000 grant for the Physics-Math building.” The project was to include 6 stories, 35 laboratories, and area for space sciences, high-energy physics, solid state, low-energy physics, and other research.[76] With the required funding secured, it was time to complete the design of the building.

Designing a New Facility

By late 1962, work on the arrangement of various aspects of the new building had been underway for more than a year. Calculation of rough figures of square footage requirements and listing building system needs had proceeded the grant proposals which included sample floor plans for the grant reviewers.

![NSF Plans - 0005 [cropped]](https://timweitzel.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/nsf-plans-0005-cropped.jpg?w=730)

NSF/NASA Proposal, 1962, p 5; University Archives,

Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall.

The initial process of designing a building is called architectural programming. This is the step where the essential of goals, wants, needs, and budget of a building are laid out for the design team. For this preliminary work, a building committee comprised of members of the department was formed to do the programming aspect of the design. The committee consisted of Richard Carlson (1913–2001), Stanley Bashkin (1923–2007), and James P. Wells (1913–1982).[77]

Carlson served as the committee chair. He was a faculty member who was appointed in 1951 and was mentioned regarding the university’s nuclear physics research. Stanley Bashkin was a faculty member appointed in 1953 and also worked in nuclear physics. He resigned and took a position with the University of Arizona in 1962.[79] Wells was an editorial assistant for the University of Iowa News and Information Service from 1952 until 1958, when he was appointed as an administrative assistant in the Department of Physics and Astronomy from where he retired in 1979. Wells prepared articles and news releases regarding the launching of University of Iowa satellites and other projects from 1958 to 1963 and following this conducted other administrative services. The building committee compiled much of the measurements and queried staff and faculty and noted requirements in a rough layout also submitted to the NSF and NASA in the grant proposals.[78]

As a guide to their programming work, the building committee consulted the volume Modern Physics Buildings: Design and Function.[80] This hardbound volume calls for many of the same items cited as desirable by the departmental faculty and staff: demonstration lecture halls, instructional laboratories, advanced instruction space (meeting rooms and laboratories), and research and academic support facilities such as a library, shops, loading areas, elevators, colloquium rooms, and administrative offices.[81]

The book is essentially a step wise review of exemplary buildings and how their qualities could be applied to building design for physics buildings, combined science buildings, or commercial research buildings. Essential to the development of Van Allen Hall would have been the chapters involving staff input in the design process, including planning aids and design tools. Also included were working drafts of sample floor plans for various rooms and facilities including lecture hall elevations, which are vertically arranged plans. The samples included 15 physics and physics-mathematics buildings, 10 combined sciences buildings—including engineering, four industrial research laboratories, and four buildings in the design process.[82]

The book also outlined building systems recommendations, especially for radioactive containment, electrical connections, mechanical connections, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning.[83] The book went as far as to recommend a subscription list of periodicals for the library.[84] Also key in the advice provided is discussions of physical space distribution and circulation needs and the suggestion to build facilities in segments allowing for funding to keep pace with the expenses of construction and equipment.[85]

What the book did not include was recommendations for the amount of space to be given to various uses, though those could be surmised from the sample floorplans. No specification was made as to the architectural style of the building and example buildings ranged widely from Neoclassical to Modern in tastes.[86] Given the record of the associate architects, it was clear their influence is evident in the final design of the building, including many choices for executing the structural elements of the building.

Physics-Mathematics Building.

“The Physics-Mathematics Building will greatly aid SUI’s Space Age commitments.”

Iowa Alumni Review, October 1963

Bids for the design of the new building were requested with estimates for the anticipated cost range made by the University Architects George Horner and Richard Jordison of near $30 per square foot at around 83,200 square feet of total space.[87] Durrant and Bergquist, the same firm that had designed the Nuclear Research Laboratory, were selected as the associate architectural firm to complete the design.[88] Durrant and Berquist had a long history of public funded design work and their creativity is evident in the design of the new building.[89] A concept sketch of their proposed design was published along with the announcement of funding received.[90] In his history of the department, James Wells stated,

The building was to have a timeless quality, avoiding modes of fashion. It was not to appear glossily new when first occupied nor antiquated too early in the 21st century. Somehow the outlines and colors should become an intermediate phase between the classic limestone structures of the central campus and the tan and red brick [of Seashore Hall to] the east.[91]

Due to various factors, ranging from funding to space allocation on the University of Iowa campus, the design sketched out in the grant proposals changed. By October 1963, a rendering of the proposed building no longer showed the second wing for classroom

![NSF Plans - 0002 [cropped]](https://timweitzel.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/nsf-plans-0002-cropped.jpg?w=424&h=308)

NSF/NASA Proposal, 1962, p 2; University Archives, Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall. Shown are the Acclerator tower as a cross hatched square area, The hatched rectangle of the proposed buidling across the top, and a proposed future addition, detailed in a press release of Feb 10, 1962 as the Educational Data Processing Center.

Bids were opened for the new Physics Research Center in early October 1963.[93] Viggo M. Jensen Company of Iowa City submitted the low bid at $908,000, which was much lower than the cost estimates.[94] This in turn lead to speculation in the department that the university had padded their cost estimates with hopes of retaining some of the extra funds.[95] Van Allen quickly sought to make use of the left over funds by adding a floor to the building and using the remaining surplus of grant money to buy equipment.[96]

In a carefully structured letter of memorandum to the University Business Office from November 8, 1963, Van Allen noted his meeting with President Hancher the previous day, stating that that they had come to the agreement for the seventh floor to be added to the proposed Physics Research Center and an additional, third floor for the astronomy research observatory that was being built southwest of Hills, Iowa.[97] In the letter he lists the proposed uses of the building and the need for additional space, including space sciences, instrument development, data analysis, nuclear physics, particle acceleration, theoretical physics, quantum field theory, statistical mechanics, and exploration of the structure of complex nuclei as well as radio astronomy when the equipment was not being used for telemetry and data transmission for the space science program.

Van Allen stated the new solid state program in particular required more space than originally planned and he stated he anticipated low temperature, high energy, and chemical physics would be added in the new research building. He notes the new equipment to include a large magnet—documented elsewhere as weighing two tons and having pole faces a foot in diameter, and a heavy equipment room as well as space for theoretical astrophysics. He reiterated that the federal funding for the Physics Research Center came to $1,083,000.

Despite the confident tone of the letter, apparently not all was sitting right with Van Allen. The Business Office had decided to create a program known as indirect costs, which effectively was a direct deduction from all external funds that would be paid by the recipient department as a set percentage of the grant or contract that went into the general fund of the university for the operation and maintenance of facilities and administration. Van Allen was clearly unhappy that out of a $1.4M annual income from federal programs, $150,000 or almost 11 percent went to “overhead charges.” This policy became the norm for the university and exists today but it was a long source of contention for Van Allen with the administration, writing at one point,

[Indirect costs were] an improper [policy] for dealing with grants and research contracts, which are obtained by individual investigators or alliances of investigators for academic work in specific areas.[98]

At another point Van Allen wrote that funds were being “piped off” with no guarantee that the funds would be used for, say, his department’s library or other items to improve the department’s research and teaching capabilities. In his memoir, university administrator D.C. Spreistersbach contended that the indirect costs pay for power, lighting, and heating and shared services such as the university libraries and computing centers.[99]

That the computing center was funded in this way was another point of contention for Van Allen. Use of digital computers was greatly expanding in the 1960s and the early 1970s. The use of these computers for data analysis had been pioneered at the University of Iowa by the Department of Physics and Astronomy for faculty and student research as well as the Iowa Testing Program run by E.F. Lindquist.

On Van Allen’s side of that equation, computers were used to calculate data in space experiments from 1960 forward. Joseph Kasper (1920–2001), then a graduate student in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, had completed his PhD thesis in 1959 using an IBM Type 704 computer that was located in Detroit, Michigan. He used the computer to calculate the trajectories of around 2,000 charged particles in a magnetic field. His results were published in 1960. Previously this kind of work had to be done with oscillographs and the calculations were all performed manually.[100] Digital computers saved enormous amounts of time and effort.

In addition to graduate research, the department began processing satellite data using computers allowing for more timely discoveries. It was for these reasons that a computer center was proposed to be built adjacent to both the new physics and astronomy building and Seashore Hall where the College of Education’s testing researchers worked.[101] But increasingly academic use of computer equipment was being directed toward student instruction.[102] Soon, the university would invest in the University Computing Center and the facility planned to be shared by space physics and the Iowa Testing Program wasn’t built. Instead the center was eventually incorporated into a new building for the College of Education as the Weeg Computing Center.

Carl McIlwain and New Data Processor Equipment, The University of Iowa, September 9, 1960. Frederick W. Kent, Iowa Digital Library, University of Iowa Archives

Despite that, Van Allen continued to champion computer equipment that was primarily intended for physics and astronomy use. Van Allen proposed that departments should be allowed to purchase their own equipment provided they could maintain it, fund it, and that it more directly served the needs of the department.[103] Ultimately, The department did succeed in owning and maintaining their own computing equipment, which began before 1965 and continued through the 1990s.[104]

The differences between department and administration to one side, the university highly publicized the receipt of the NSF and NASA grants in press releases and in alumni publications. Construction started on the new Physics Research Center at the end of October of 1963.[105] It would have been easy to ignore the ground clearing activities near Jefferson and Dubuque streets in the flurry of construction occurring at the time and over the next three years on campus. The Nuclear Physics Laboratory was already under construction next door to the new building site and active construction sites for Phillips Hall and the addition to the biology building were nearby.

Constrution on the Original Section of Van Allen Hall, July 1964. Frederick W. Kent, Iowa Digital Library, University of Iowa Archives.

By the time the new physics and astronomy building was under construction it was agreed that mathematics would remain in Maclean Hall.[106] The old physics building was renamed Mathematical Sciences Building around 1967, signalling the intent for the building to become primarily the home of the Mathematics Department. That incidentally lasted just two years. By 1969, the building was renamed MacLean Hall at the same time that University Hall was renamed Jessup Hall.[107] In addition to the Mathematics Department, MacLean would also eventually house the new Computer Science Department. Classroom and laboratory space for undergraduate instruction in physics and astronomy stayed in MacLean Hall from 1965 to 1970.

From the distance of time, the construction pace for a seven story building in what was then a relatively new technique—a reinforced concrete superstructure clad with precast concrete wall units, seemed ambitious. In some anecdotes of staff members from that time, there were a few mistakes made. For instance, at one point a section of forms were removed before the concrete had fully achieved strength and a floor collapsed.[108] But progress seems to have been good just the same.

As late as October 1964, there were news reports stating the building would not be completed until some point in 1966.[109] The construction of the Physics Research Center was actually completed ahead of that estimate in the fall of 1965.[110] Moving occurred primarily in August of that year, though some furnishings and equipment began to arrive as early as June and some of the interior spaces of the building were not completed until later in the year, especially the finish work on the first floor and basement.[111]

Additional amenities included a research library, a colloquium room with walnut furniture, a conference room with a 16.5-ft table, a commons, a large machine shop with 40 floor tools and a crane to position equipment where it was needed for workflow. There were three auxiliary shops, a computing center on the second floor and a publications office, and a main entry with 10 glass display cases. Basement rooms, shielded from cosmic rays for testing and calibrating space instruments held an electronic shaker drum, an X-ray transformer, an environmental chamber, and the 2 MeV Van de Graaff linear accelerator for space instrument testing brought over from MacLean Hall.[112]

The 1970 addition was begun in 1967. The pace of construction was again timely with construction taking just over two years to complete. A temporary delay of construction

![20170619_090427 [Web Large]](https://timweitzel.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/20170619_090427-web-large-1.jpg?w=417&h=235)

Van Allen Hall, view facing northwest. Tim Weitzel

![20170619_090713 [Web Large]](https://timweitzel.files.wordpress.com/2019/09/20170619_090713-web-large-1.jpg?w=448&h=252)

Lecture Room II, Van Allen Hall. Tim Weitzel

The addition was intended for instructional use and would reunite all aspects of the department in one building. The proposal included student laboratories, general use classrooms and lecture rooms, and a half-floor for the Science Education Center of the College of Education.[117]

Other External Funding

Other federal programs matched to state appropriations would be utilized for the 1970 classroom addition to the building. Planning for new classroom space had begun at about the same time as the research building, but funding sources were harder to find for undergraduate instruction at that time. Regardless, by 1966 serious consideration was being given to the classroom addition of the building that had been shown in the first concept sketches of the building in 1962.[120] In September 1967, The Board of Regents approved the $2.45M addition for physics and astronomy with DDDK&G as architects and Fane F. Vawter and Company selected as general contractor.[121] DDDK&G was the successor firm to Durrant and Berquist.[122]

To the consternation of the department, the College of Education space in the 1970 addition expanded by 1975 to much more area than originally planned at the expense of the Physics and Astronomy classroom space. Part of this point of contention was the perception that once again grants secured by Van Allen had made the building possible and the University was taking an unfair portion of it for other uses. But similar to the original portion for the building, a substantial appropriation from the state had been part of the funding. Where Van Allen had secured $739,497 for the addition from two grants through the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, a much larger sum of $1.71M was appropriated by the Legislature in the Spring of 1967.[118] The HEW funding was made available through an expansion of the Higher Education Facilities Act of 1963, which funded buildings for undergraduate instruction.[119]

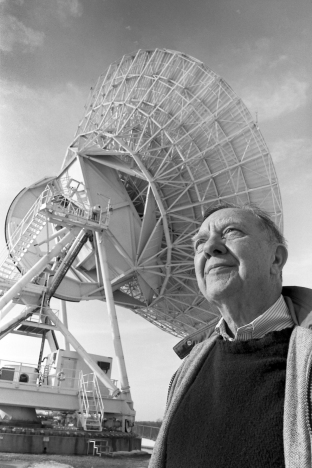

In 1966, another opportunity for a different type of funding for facilities arrived as a one-off event. The University of Iowa ran a robust series of low earth orbit experiments through the 1960s into the late 1970s. A station for receiving satellite data had been built southwest of Hills around 1965. The station consisted of a radio dish mounted on a surplus WWII gun armature and that on a tower designed by University of Iowa engineering faculty member Ned Ashton. This was emblematic of the UI Space Science program, a can-do attitude for science, with military left-overs and unique funding sources conducted in the midwestern fields of Iowa.

A utility company was constructing an electric power transmission line just north of Hills, Iowa. Antennas work by receiving or emitting radio and other electromagnetic

Hills Tracking Station, Iowa Alumni Review, October 1964

signals outside of the visible spectrum. Power transmission lines create strong electrical and a magnetic field in their vicinity. The electrical field of the line was strong enough that it interfered with the sensitive satellite receiver and radio astronomy research antenna that was located at the research observatory.

The private company offered to provide $85,000 as financial assistance to relocate the antenna elsewhere.[123] This resulted in a new radio observatory and satellite data receiving station on land rented from the US Army Corps of Engineers northeast of North Liberty, Iowa. A new 60-foot dish was bought and the older dish and tower moved to the new location. The results were a new facility, done with as much money put toward science as possible by saving expenses in creative ways. The antenna was later replaced in 1986 when operations of the North Liberty observatory were transferred to the Long Baseline Observatory and a new 82-foot dish was constructed.[124]

Van Allen at the North Liberty Radio Observatory with one of 10 twenty-five-meter radio-telescope antennas across the globe that make up the Very Long Baseline, February 1994. Tom Jorgensen, University of Iowa Office of University Relations.

Van Allen Hall’s Legacy

Van Allen Hall has been important to the history of the university and national space program, which has grown from a small, provisional cosmic radiation laboratory at the end of the basement in Maclean Hall into an advanced set of workshops and clean rooms to create instruments and vessels in low earth orbit and exploration of the solar system and beyond. Many instruments have been and continue to be built utilizing the machine shops and electronics assembly shops in the building.[125]

With the successes of several Explorer and Injun experiments behind them and a new building being occupied by early September 1965, the Department of Physics and Astronomy quickly began to shift the focus of the department’s activities and identity there. But the academic side of the department remained unsettled by the separation of classroom space in MacLean Hall from the faculty offices in the Physics Research Center until the classroom addition was completed in 1970.[126]

Although the department has always had multiple areas of research interests, including nuclear and particle physics, solid state research, and radio and optical astronomy—space science is among the top achievements of the University of Iowa in securing new knowledge of broad importance to both the public and the scientific community. The magnetospheric and planetary plasma physics, both aspects of space physics, in particular were pioneering and world class.[127]

Van Allen was very confident in the abilities and contributions of the University of Iowa to the US space science program. In 1981, he offered the following opinion,

[We are] the leading university in the world in the field. There have been more flights, more fundamental discoveries and more work done here than at any other university in the world.[128]

The success of the department is the result of significant contributions to science as well as continued public advocacy, a demonstrated ability to secure funding, and a strong commitment to educating new researchers and academic scientists. At the same time, Van Allen remained somewhat humble about his own presence in the department, stating that,

The Department of Physics and Astronomy is in good shape. I could possibly disappear and nobody would miss me. We have some very good younger people, and some not so terribly young any more, like Lou Frank and [Donald] Gurnett and others. I got them all started.[129]

Van Allen taught many individuals who, after obtaining their advanced degrees at the University of Iowa, have gone on to contribute significantly to the fields of physics and space research, two of which include prominent professors in physics at the University of Iowa—Lou Frank (1939–2014) and Donald Gurnett.

While continuing their ongoing research missions with the Pioneer, Injun, and Mariner line of missions, the department began to prepare the next generation of space science instruments for which Van Allen and his former graduate students were instrumental in designing.[130] Frank in particular was in charge of the Low-energy Proton Electron Differentiating Electrostatic Analyzer and Gurnett worked on detecting radio waves in electric fields with his hallmark antenna array. They were detecting specifically space plasma where the electrons are separated from the atom forming ions and the two freely circulate within the field. This has implications for both the study of magnetospheres around certain planets but also differences in local space, such as the Heliopause at the edge of the Solar System. The successes of the 1960s were the foundation for success in the 1970s and those successes in turn have carried on to the present, now more than 50 years since the building was first occupied.

The department placed instruments on spacecraft that visited most of the eight planets and other objects in the solar system. Those instruments were designed, built, and tested in Van Allen Hall. While Van Allen continued to daily monitor the data from instruments onboard Pioneer 10 and 11, which also were designed at Van Allen Hall, Gurnett and Frank designed other instruments for other missions, including the Plasma Diagnostic Package which was the first probe released and recaptured by the Space Shuttle program as well as instruments on Voyagers 1 & 2, a comet exploration mission, Mariner Venus Probe, Galileo, and Cassini.

The students of these two professors have gone on to contribute significantly to space physics research as well, holding key positions at NASA and at research universities, as academic professors, and as corporate researchers and designers of space flight instruments. Others with doctorates work on the current instrument missions for the University of Iowa, such as the Mars Express mission, Juno, and Craig Kletzing’s Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites (TRACERS), which is part of NASA’s Explorers Program studying how the sun affects space and the space environment around planets and is the largest grant ever awarded to the University of Iowa.[131] Other graduates work at the private research using the Hubble Telescope, design electronics for public and private space flight at Collins Aerospace, teach college level physics and astronomy, and work with or for various divisions of NASA, including the Wallops Flight Facility and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Prominent graduates include Jim Green (PhD 1979), NASA Planetary Science Division Director and William Ferrall, (PhD 1987), plasma physicist in the Solar System Exploration Division at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Changing Names

Van Allan Hall was initially named Physics Research Center and the addition completed in 1970 initially went by the name Physics Research Center II. In May of 1971, the name of the building was formally changed to Physics Building.[132] There is speculation that the name change may have been due to civil unrest related to the Kent State shootings on May 4, 1970 and other potential liabilities from being a known research facility.[133] There is also indication that the building was informally called the Physics Building from 1965 and the change simply honored that fact.[134]

In 1981, a campaign led by rhetoric instructor Steven Vibbert was successful in renaming the Physics Building to Van Allen Hall. The name change was approved by the Board of Regents the following year.

The naming of a building for a living person who was still the department chair was unprecedented. Speaking to the Daily Iowan in 1980, Vibbert described how he came up with the idea to rename the Physics Building in honor of Van Allen. He said the University of Iowa has three goals—Education, Service, and Research and that no one has been the example that Van Allen set by continued teaching excellence, unquestionable research, and helped both Iowa City and the World.[135]

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the following people for reviewing this article for content: Bruce Randall, George Hospedarsky, James Kasper.

Sources

Barlow, Charles and Wayne Faupel. Acts and Joint Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Fifty-eighth General Assembly of the State of Iowa. Des Moines: State of Iowa, 1959. https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/iactc/58.1/1959_Iowa_Acts.pdf

Acts and Joint Resolutions Passed at the Regular Session of the Fifty-ninth General Assembly of the State of Iowa. Des Moines: State of Iowa, 1961. https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/iactc/59.1/1961_Iowa_Acts.pdf

Brcak, Nancy and Jean Sizemore. The “New” University of Iowa: A Beaux-Arts Design for the Pentacrest, Annals of Iowa, Vol. 51, No. 2, 1991.

Foerstner, Abigail. James Van Allen: The First Eight Billion Miles. University of Iowa Press. 2007.

Gerber, John. A Pictorial History of the University of Iowa: An Expanded Edition. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2005.

Green, Constance and Milton Lomask. Vangaurd: A History, The NASA Historical Series, Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1970. https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4202.pdf

HEW. A Common Thread of Service: A History of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, excerpt from US Department of Health, Education and Welfare publication no. (OS) 73-45, July 1, 1972. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/common-thread-service/history-department-health-education-and-welfare.

Kennedy, John F. Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs, May 25, 1961. https://www.jfklibrary.org/asset-viewer/archives/JFKPOF/034/JFKPOF-034-030

Report to the Congress from the President of the United States, United States Aeronautics and Space Activities, 1962. https://history.nasa.gov/presrep1962.pdf

Lewis, Richard. UI wins its largest-ever research award, Iowa Now. https://now.uiowa.edu/2019/06/ui-wins-its-largest-ever-research-award

Mazuzen, George. Chapter 3, The National Science Foundation: A Brief History, 1994. https://www.nsf.gov/about/history/nsf50/nsf8816.jsp

Miller, Wiliam. Supplement to Revised and Annotated Code of Iowa Containing Acts and Resolutions of the Twenty-third General Assembly. Des Moines: Mills Publishing Co., 1890. https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/shelves/acts/ocr/Iowa%20Acts%2023GA%20(1890).pdf

Newell, Homer. Beyond the Atmosphere: Early Years of Space Science, Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1980. https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4211/cover.htm

Personal Communications

Randall, Bruce, PhD. January 5, 2014.

Suszcynsky, David, Ph.D. January 7, 2014.

Pickard, Josiah. Historical Sketch of the State University of Iowa, Annals of Iowa, vol. 4, no. 1, pp 1–66, 1899. https://doi.org/10.17077/0003-4827.2347

Scott, John and Rodney Lehnertz. The University of Iowa Guide to Campus Architecture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2006.

Spriestersbach, D.C., The Way it Was: The University of Iowa 1964–1989. University of Iowa Press, Iowa City, 1999.

Task Force to Assess NASA University Programs. A Study to Assess University Programs, Washington, D.C: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1968. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19680026092.pdf

Van Allen, James. My Life at APL, pp. 173–177. Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1997. https://www.jhuapl.edu/Content/techdigest/pdf/V33-N03/33-03-Krimigis.pdf

Van Nimmen, Jane, Leonoard Burno, and Robert Rosholt, NASA Historical Data Book: 1958–1968, Vol 1, NASA Resources, Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 1976. https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4012v1.pdf

Weitzel, Tim. The Architectural Firms of Joseph George Durrant, On Diverse Arts and Sciences, March, 2017. https://timweitzel.wordpress.com/2017/03/31/the-architectural-firms-of-joseph-george-durrant/

Wells, James P. Annals of a University of Iowa Department: From Natural Philosophy to Physics and Astronomy. Unpublished manuscript. Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa. 1980. http://www-pw.physics.uiowa.edu/ProfVanAllen/annals_UI_NaturalPhilosophyToPhysicsAstronomy.pdf

[1] Sputnik 1 was the first human made object in space and this began the space age on October 4, 1957. Sputnik 2 carried the dog Laitka into space on November 3, 1957 and was the first biological experiment in space.

[2] Wells, 1980, p 190; ; MacLean Hall was originally named Physics Building. It was also known as Mathematical Sciences Building after 1966. It was Renamed Maclean Hall around 1969. For buildings, the dates indicate completion of construction and dates of major alterations or demolition. For people, dates in parenthesis indicate birth and death for a deceased person.

[3] University of Iowa Archives, Enrollment Frequently Asked Questions. http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/sc/archives/faq/faqenrollment

[4] Wells, 1980, p 190; NSF/NASA Proposal, 1962, p 7; University Archives, Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall. The Physics building, completed in 1912, was the third building where physics was taught. It was renamed MacLean Hall around 1969. Until 1967, it was known only as the Physics Building.

[5] Palmer and Rice, 1961, p 1.

[6] Daily Iowan, Sep 19, 1958, p 1. Iowa Alumni Review, Aug 1964, p 2.

[7] Wells, 1980, p 190.

[8] Iowa Digital Library, Proposed Physics-Mathematics Building on Pentacrest, The University of Iowa, August 19, 1958, Frederick W. Kent Collection of Photographs, 1866-2000, Collection ID.: RG30.0001.001, file name.:bldgs172-0008.jpg

[9] Iowa Digital Library, Proposed Physics Building on Pentacrest, The University of Iowa, August 19, 1958, Frederick W. Kent Collection of Photographs, 1866-2000, Collection ID.: RG30.0001.001, file name.: bldgs172-0007.jpg

[10] Wells, 1980, p 197.

[11] Pickard, 1899, p 36.

[12] Daily Iowan, Sep 19, 1958, p 1.

[13] Daily Iowan, Dec 11, 1958, p 1; Daily Iowan, Dec 11, 1958, p 1.

[14] At this time the University of Iowa was officially the State University of Iowa; Daily Iowan, Dec 11, 1958, p 1.; Daily Iowan, Dec 10, 1958, p 1; Daily Iowan, Sep 19, 1958, p 1.

[15] Daily Iowan, Sep 19, 1958, p 1.

[16] Biographical Dictionary of Iowa, Loveless, Herschel C.; Daily Iowan, Feb 10, 1959, p 2.

[17] Barlow and Faupel, 1959, p 36.

[18] Daily Iowan, Nov 11, 1959, p 1.

[19] Brcak and Sizemore, 1991, pp 149–167; National Register of Historic Places Reference No.: 78001230.

[20] Daily Iowan, Dec 10, 1958, p 2.

[21] Daily Iowan, Mar 15, 1961, p 6.

[22] Daily Iowan, Mar 15, 1961, p 6.

[23] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 227.

[24] Wells, 1980, pp 136, 143.

[25] Van Allen, 1997;

[26] Biographical Dictionary of Iowa, Erbe, Norman A.

[27] Daily Iowan, Mar 15, 1961, p 6.

[28] Miller, 1890, p 167.

[29] Wells, 1890, p 4.

[30] Analogously to Congressional jurisdiction for Washington, D.C., the State of Iowa still controlled Iowa City at the time; History of Johnson County, Iowa, 1883, p 381.

[31] Gerber 2005, p 77.

[32] Pickard, 1899, p 27.

[33] Manshiem, 1989, p 157; Gerber 2005, p 77.

[34] Gerber 2005, p 78.

[35] Daily Iowan, Mar 15, 1961, p 6.

[36] Pickard, 1899, p 27.

[37] Daily Iowan, May 14, 1973, p 10; Daily Iowan, Jun 12, 1974, p 3.

[38] Daily Iowan, Mar 10, 1961, p 1.

[39] Daily Iowan, Mar 15, 1961, p 6.

[40] University of Iowa press release, Dec 21, 1966; Daily Iowan, Dec 21, 1966. A good description of how this particular accelerator worked was provided by Lynn Sampson in the Daily Iowan, May 21, 1963, p 3. http://dailyiowan.lib.uiowa.edu/DI/1963/di1963-05-21.pdf. Further descriptions are provided in an article on July 4, 1964, pp 1, 8. http://dailyiowan.lib.uiowa.edu/DI/1963/di1963-07-04.pdf.

[41] University of Iowa press release, Dec 26, 1961.

[42] Bruce Randall, personal communication

[43] Daily Iowan, Dec 21, 1966, p 4.

[44] University of Iowa press release, Sep 26, 1997.

[45] Daily Iowan, November 19, 1965; Spreistersbach, 1999, p 13.

[46] Daily Iowan, March 11, 1961, p. 3

[47] Barlow, 1961, p 37.

[48] Barlow, 1961, p 37.

[49] NSF/NASA Grant Proposal, 1962, University Archives, Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall.

[50] Mazuzan, 1994.

[51] University of Iowa press release, Sep 22, 1962; Jan 12, 1963; Daily Iowan, Nov 14, 1962, p 7.

[52] Newell, 1980, p 226.

[53] Newell, 1980, p 225.

[54] Kennedy, 1962, p 29; University of Iowa Press Release, Sep 22, 1962.

[55] Van Nimmen, Burno and Rosholt, 1976, pp 134,136. Newell, 1980, Chs 13, 14.

[56] Task Force, 1968, p 57.

[57] NSF/NASA Proposal, 1962, p 1; University Archives, Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall.

[58] Task Force, 1968, p 56.

[59] National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 (PL 85–568).

[60] Mazuzen, 1994.

[61] Kennedy, 1961.

[62] Logsdon, 2011.

[63] Mansheim, 1989, p 193; Gerber 2005, p. 165; Scott and Lehnertz, 2006, p 235; The Nuclear Physics Building was completed in 1964, The first part of Van Allen Hall was not completed until 1965, however the University records group the two as a single building creating confusion over the completion date for Van Allen Hall; Information for the period following 2006 has not been published.

[64] Spreistersbach, 1999, p 230.

[65] Foerstner, pp 2007, 77, 137, 231; Daily Iowan, Jan 3, 1958, p 1; Green and Lomask, 1970, p 97.

[66] Spreistersbach, 1999, p 228.

[67] Spreistersbach, 1999, p 227.

[68] NSF/NASA Grant Proposal, 1962, University Archives, Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall.

[69] Spreistersbach, 1999, p 228.

[70] Iowa Alumni Review, Oct 1962, p 4.

[71] Daily Iowan, Sep 25, 1962, p 2; Iowa Alumni Review, Oct 1962, p 6.

[72] Wells, 1980, p 190.

[73] Daily Iowan, Nov 14, 1962, p 7;

[74] Daily Iowan, Nov 14, 1962, p 7; Iowa Alumni Review, Oct 1963, p 10.

[75] Daily Iowan, Nov 14, 1962, p 7.

[76] University of Iowa press release, Jan 12, 1963; Wells, 1980, p 212.

[77] Wells, 1980, p 211.

[78] NSF/NASA Grant Proposal, 1962, University Archives, Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall.

[79] Wells, 1980, p 197.

[80] Wells, 1980, p 207.

[81] Palmer and Rice, 1961, p 4; c.f. Wells, 1980, p 209.

[82] Palmer and Rice, 1961, p 15; p 24; p 26; p. 56; p 137.

[83] Palmer and Rice, 1961, p 283; p 31; p 35; p 42, 145.

[84] Palmer and Rice, 1961, p 11.

[85] Palmer and Rice, 1961, p 25; p 20.

[86] As examples, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, University of Virginia, Charlottesville; Colorado State University, Brigham Young University, University of Georgia.

[87] Wells, 1980, p 211.

[88] University of Iowa press release, Sep 15, 1962; Daily Iowan, Feb 10, 1962, p 1.

[89] Weitzel, 2017.

[90] Daily Iowan, Nov 11, 1962, p 7.

[91] Wells, 1980, p 210.

[92] Iowa Alumni Review, Oct 1963, p 10.

[93] Wells, 1980, p 213; Daily Iowan, October 9, 1963, p. 5.

[94] Daily Iowan, October 9, 1963, p. 5.

[95] Wells, 1980, p 213.

[96] Daily Iowan, Nov 16, 1963, p. 6.

[97] Letter of Memorandum from James Van Allen to University of Iowa Business Office, Nov, 8, 1963.

[98] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 6.

[99] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 49; Spriestersbach was dean of the UI Graduate College from 1965 to 1989 and served as vice president for research, vice president for educational research and development, and acting president of the university.

[100] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 155.

[101] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 50.

[102] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 51.

[103] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 161.

[104] Spriestersbach, 1999, p 155.

[105] Wells, 1980, p 214.

[106] Wells, 1980, p 208.

[107] Daily Iowan, Sep 16, 1967, p. 1. ; University of Iowa campus map, 1967, from Catalogue of the State University of Iowa: 1967, Iowa Digital Library, collection ID, RG01.08, file name 1967.jpg. University of Iowa campus map, 1968, from Catalogue of the State University of Iowa: 1968, Iowa Digital Library, collection ID, RG01.08, file name 1968.jpg. University of Iowa campus map, 1969, from Catalogue of the State University of Iowa: 1969, Iowa Digital Library, collection ID, RG01.08, filename 1969-2_Index.jpg.

[108] Bruce Randall, personal communication.

[109] Daily Iowan, Oct 27, 1964, p 6.

[110] University of Iowa Historic Buildings Inventory, Buildings and Grounds Vertical Files, University of Iowa Archives, The University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa.

[111] Wells, 1980, p 216.

[112] Wells, 1980, p 219; Bruce Randall, personal communication.

[113] Foerstner, 2007, p . 238; Wells, 1980, p 225.

[114] Wells, 1980, p 226.

[115] Wells, 1980, p 227; Weitzel 2017.

[116] Daily Iowan, Sep 16, 1967, p. 1

[117] Daily Iowan, Sep 16, 1967, p. 1; Wells, 1980, p 226.

[118] Daily Iowan, Sep 16, 1967, p 1; Spriestersbach, 1999, p 231; Wells, 1980, p 225.

[119] Higher Education Facilities Act of 1963, as amended PL 88-204. The 1966 amendment allowed art costs to be counted in the development cost of facilities (PL 89-752), while a 1965 law doubled the funds available for 1966 grant cycle (PL 89–329); HEW, 1972.

[120] NSF/NASA Grant Proposal, 1962, University Archives, Campus Buildings and Grounds Vertical File, Van Allen Hall.

[121] Daily Iowan, Sep 16, 1967, p. 1

[122] Weitzel, 2017.

[123] University of Iowa press release, Oct 8, 1966.

[124] Iowa Alumni Review, Mar-Apr 1986, p 10.

[125] Foerstner, 2007, p. 207.

[126] Wells, 1980, p 223.

[127] David Suszcynsky, personal communication

[128] Iowa Alumni Review, February–March, 1981, p 12.

[129] Iowa Alumni Review, February–March, 1981, p 12.

[130] Wells, 1980, p 233. Synopsis of the various programs are provided here: Pioneer, Mariner, University of Iowa Injun and Hawkeye (Explorer 52).

[131] Lewis, 2019.

[132] University of Iowa press release, May 15, 1971.

[133] Daily Iowan, July 29, 1983.

[134] Bruce Randall, Personal Communication.

[135] Daily Iowan, Apr 8, 1980, p. 1

American Indian Archery Technology

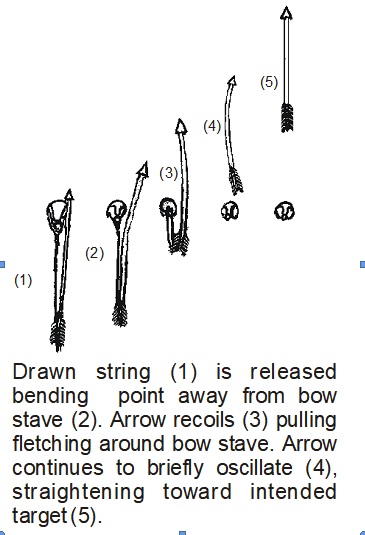

Although projectile points found on archaeological sites are commonly referred to as “arrow heads” American Indians* did not always have the bow and arrow. It was not until about A.D. 500 that this technology was adopted. Other tools were used in the more than 10,000 years previous to this. The first projectiles people used in Iowa were likely spears. The main advantages of the bow and arrow compared to the spear are more rapid missile velocity, higher degree of accuracy, and greater mobility. Arrowheads also required substantially less raw materials than spear heads. A flint knapper could produce a large number of small projectile points from a single piece of chert. Bow and arrow technology was retained into the early part of the Historic Period.

Although projectile points found on archaeological sites are commonly referred to as “arrow heads” American Indians* did not always have the bow and arrow. It was not until about A.D. 500 that this technology was adopted. Other tools were used in the more than 10,000 years previous to this. The first projectiles people used in Iowa were likely spears. The main advantages of the bow and arrow compared to the spear are more rapid missile velocity, higher degree of accuracy, and greater mobility. Arrowheads also required substantially less raw materials than spear heads. A flint knapper could produce a large number of small projectile points from a single piece of chert. Bow and arrow technology was retained into the early part of the Historic Period.

In some instances, as recorded by Jesuit missionary-explorer Père Claude Aloués, bows continued to be used after the introduction of guns. Even with the many advantages of guns, bows and arrows are much quieter and much more rapid than early muzzle-loading guns, allowing the hunter more chances to strike at the prey. Indians used arrows to kill animals as large as bison and elk. Hunters approached their prey on foot or on horseback, accurately targeting vulnerable areas.

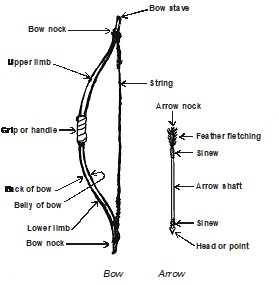

Bow and Arrow Terminology

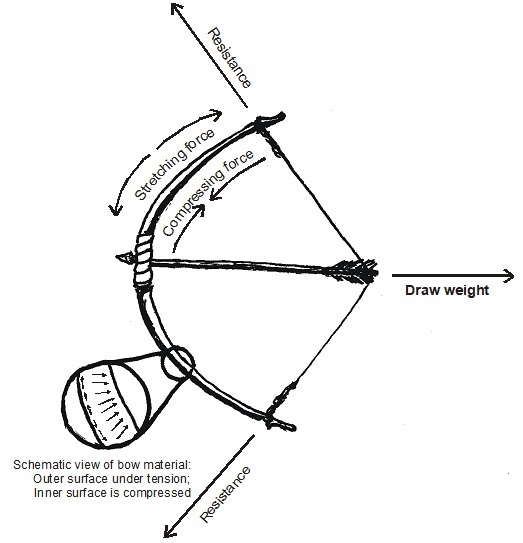

Raw materials were not randomly chosen for constructing bow and arrows. Some materials were generally more readily available than others. Humidity alters the effectiveness of wooden bows. Temperature affects horn and antler. The intended use of the bow and arrow system, on foot or horse back, for instance, affects the final design. Bows used while mounted on horseback tend to be shorter than bows used when on foot.

The length of the bow determines the amount and kinds of stress placed on the bow when drawn. For this reason, shorter bows tend to be made of composites of different materials while bows used when on foot tend to be made of wood. Indians used a variety of materials to make the bow stave, relying on materials that met certain requirements, the most important of which is flexibility without breaking.

Examples of North American Bows

Several species of plants and some animal materials common to Iowa and surrounding areas met these requirements. Ash, hickory, locust, Osage orange, cedar, juniper, oak, walnut, birch, choke cherry, serviceberry, and mulberry woods were used. Elk antler, mountain sheep horn, bison horn, and ribs, and caribou antler also were used where available.

Bow designs used included a single stave of wood (self bow), wood with sinew reinforcement (backed bow), and a combination of horn or antler with sinew backing (composite bow). Hide glue was used to attach the backing. Bow strings most frequently were made of sinew (animal back or leg tendon), rawhide, or gut. The Dakota Indians also used cord made from the neck of snapping turtles. Occasionally, plant fibers, such as inner bark of basswood, slippery elm or cherry trees, and yucca were used. Nettles, milkweed, and dogbane are also suitable fibers. Well-made plant fiber string is superior to string made of animal fibers because it holds the most weight while resisting stretching and remaining strong in damp conditions. However, plant fiber strings are generally much more labor intensive to make than animal fiber strings, and the preference in the recent past was for sinew, gut, or rawhide.

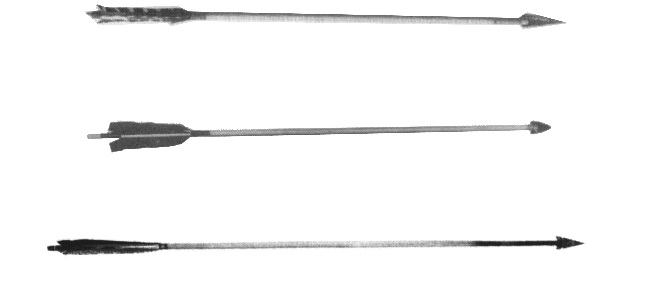

Arrow shafts were made out of shoots, such as dogwood, wild rose, ash, birch, chokecherry, and black locust. Reeds from common reed grass were also used with some frequency throughout North America with the exception of the Plains where reeds did not grow. Shoots were shaved, sanded, or heat and pressure straightened. Tools made of bone, wood, sandstone, pumice and naturally occurring clinkers or burnt lignite were used to straighten the shaft wood. Experimental archaeology has found bedrock outcrops in the Des Moines River Valley in Iowa to produce excellent raw materials for shaft-abraders.

Because they are hollow and light, reed-shaft arrows typically have a wooden foreshaft and sometimes a wooden plug for the nock end of the arrow. If a foreshaft was used, it could be glued to the main shaft, tied with sinew, or fit closely enough to not need glue or sinew.

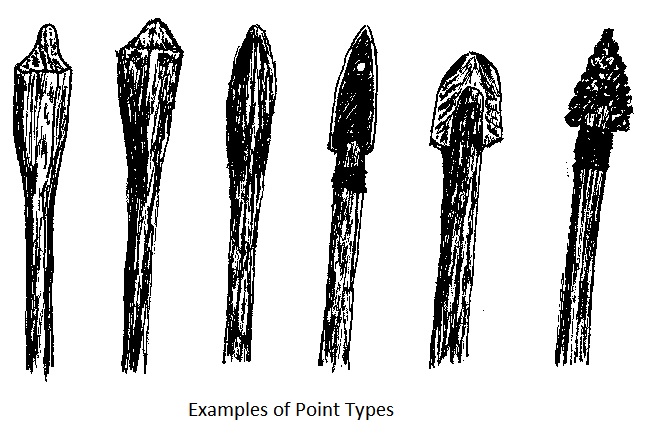

Points were attached to the arrow shaft with a variety of methods. Most frequently, the arrow shaft would have a slit cut into the end to accept the point. Sinew would then be wrapped around the shaft to pinch the slit closed. Points could also be hafted directly by wrapping sinew around the point and the arrow shaft. Metal points generally were attached using the same techniques and only infrequently attached by means of a socket.